⌾Curio #14 - Martha Gellhorn, Dancing Plague & Philip Selway

Welcome back to another edition of Curio, a refreshing afternoon sea breeze to briefly distract you from the chaotic universe of social media and the never-ending news cycle.

Garden at Sainte-Adresse by Claude Monet (1867)

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, then feel free to forward it to some friends and they can sign up below:

Have a great weekend!

Oli

Martha Gellhorn & The Trial of Adolf Eichmann

A Witness To History

Martha Gellhorn is one of the twentieth century’s most celebrated war correspondents. For over fifty years she reported from the front lines of geopolitically significant conflicts, starting at the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s (where she met Ernest Hemingway, to whom she would be married from 1940 to 1945).

Gellhorn and Hemingway

During the Second World War, she was a witness to and reporter of the Blitz in London, the D-Day invasion of Normandy and the liberation of Dachau concentration camp. Later in her career, Gellhorn covered the Vietnam War, the Nicaraguan contras, the Arab-Israeli conflict and, in her early eighties, the United States invasion of Panama. She was also a successful writer of fiction, leading the author Bill Buford to say:

''Reading Martha Gellhorn for the first time is a staggering experience. She is not a travel writer or a journalist or a novelist. She is all of these, and one of the most eloquent witnesses of the 20th century.''

Eichmann and the Private Conscience

Gellhorn, whose father was Jewish, was present in the audience at the trial in Jerusalem of senior Nazi and key mastermind of the Holocaust, Adolf Eichmann. Her 1962 essay on witnessing the trial, ‘Eichmann and the Private Conscience’, is one of the most powerful pieces of non-fiction I’ve ever read. Here are some excerpts:

In the bulletproof glass dock, shaped like the prow of a ship, sits a little man with a thin neck, high shoulders, curiously reptilian eyes, a sharp face, balding dark hair. He changes his glasses frequently, for no explicable reason. He tightens his narrow mouth, purses it. Sometimes there is a slight tic under his left eye. He runs his tongue around his teeth, he seems to suck his gums. The only sound ever heard from his glass cage is when -- with a large white handkerchief -- he blows his nose. People, coming fresh to this courtroom, stare at him. We have all stared; from time to time we stare again. We are trying, in vain, to answer the same question: how is it possible? He looks like a human being, which is to say he is formed as other men. He breathes, eats, sleeps, reads, hears, sees. What goes on inside him? Who is he; who on God's earth is he? How can he have been what he was, done what he did? How is it possible?

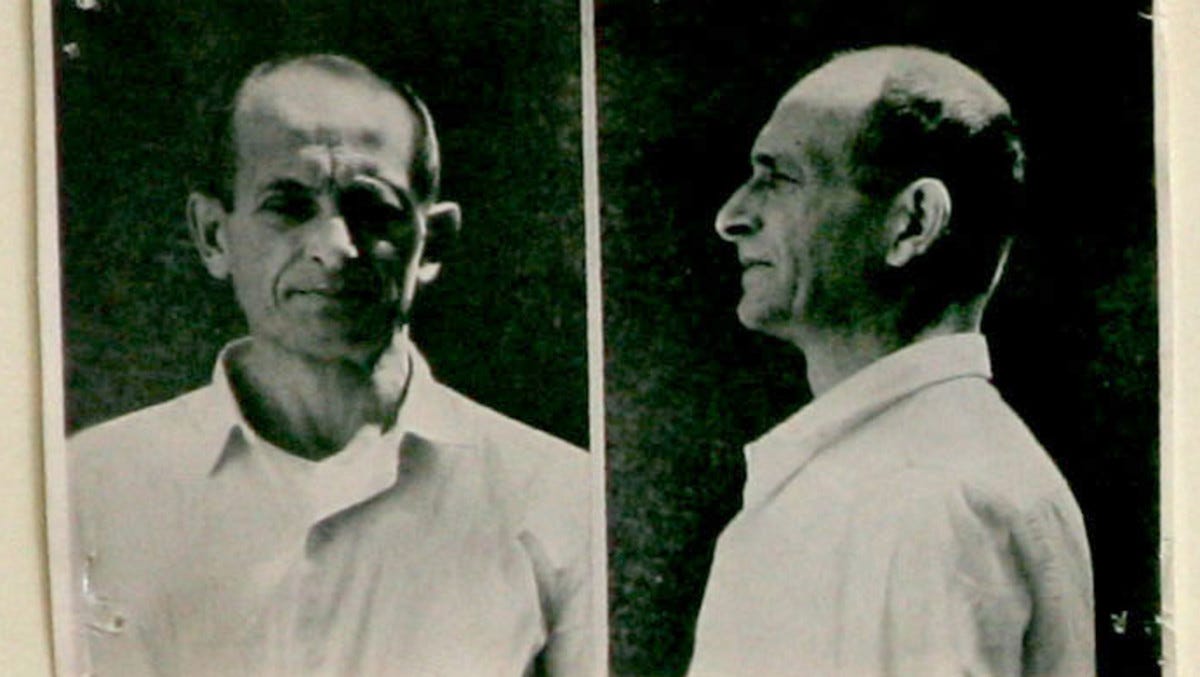

Eichmann on trial (1961)

We fear him because we know that he is sane. It would be a great comfort to us if he were insane; we could then dismiss him, with horror, no doubt, but reassuring ourselves that he is not like us, his machinery went criminally wrong, our machinery is in good order. There is no comfort. This is a sane man, and a sane man is capable of unrepentant, unlimited, planned evil. He was the genius bureaucrat, he was the powerful frozen mind which directed a gigantic organization; he is the perfect model of inhumanness; but he was not alone. Eager thousands obeyed him.

After the war, Eichmann managed to escape from the US forces. He moved around Germany to avoid being recaptured before immigrating to Argentina in 1950 under the false name of Ricardo Klement. For the next ten years, he and his family lived in Buenos Aires, where he ended up working as a laborer at a Mercedes-Benz factory. In 1960, he was captured by Mossad, Israel’s intelligence service, and put on trial.

We consider this man, and everything he stands for, with justified fear. We belong to the same species. Is the human race able -- at any time, anywhere -- to spew up others like him? Why not? Adolf Eichmann is the most dire warning to us all. He is a warning to guard our souls; to refuse utterly and forever to give allegiance without question, to obey orders silently, to scream slogans. He is a warning that the private conscience is the last and only protection of the civilized world.

Eichmann’s official Nazi portrait (1942)

Eichmann divided the world into the powers of light and darkness. He chose the doctrine of darkness, as did the majority of his countrymen, as did thousands throughout Europe -- men with slave minds, pig-greedy for power: the Vichy police, the Iron Guard, big and little Quislings everywhere. He stated their creed in one line: "The question of conscience is a matter for the head of the state, the sovereign."

Absolved of thought, of responsibility, of guilt, and finally of humanity, all is well: the head of the state thinks for us, we need only obey. If the head of the state happens to be criminally insane, that is not our affair.

The purpose of all education and all religion is to fight that creed, by every act of life and until death. The private conscience is not only the last protection of the civilized world, it is the one guarantee of the dignity of man. And if we have failed to learn this, even now, Eichmann is before us, a fact and a symbol, to teach the lesson.

The Dancing Plague of 1518

In July 1518, in the city of Strasbourg, a woman called Frau Troffea began to dance manically in the street. Without music or apparent enjoyment, she didn’t stop for days. Inexplicably, other people started joining her. Within a week, more than thirty people were involved and within a month, around four hundred. Many dancers kept moving until they collapsed and died of a heart attack, stroke or pure exhaustion. This strange but well-documented event became known as the Dancing Plague of 1518.

The local authorities were terrified and couldn’t figure out why it was happening. The two most common explanations at the time were that the participants were either possessed by demons or that they were experiencing ‘hot blood’ (whatever that means).

Historians today aren’t certain what caused this group madness seen in the mysterious dancing plague, but there are a couple of potential explanations.

That the participants had accidentally ingested ergot, a toxic mold that grows on damp rye flour. It produces spasms, psychosis and hallucinations. The theory is that those afflicted might have consumed rye bread (which was common in the area) made from the contaminated flour.

Strasbourg in 1518 was experiencing particularly terrible bouts of disease and famine. The severe stress of these conditions, combined with the superstitious mentality of the inhabitants of the area, leads historian John Waller to speculate that it was an example of stress-induced mass psychogenic illness, which is a mass hysteria involving a group of people who suddenly exhibit the same bizarre behavior which spreads like an epidemic.

Philip Selway

Phil Selway is best known for being the drummer for Radiohead. And like other members of that remarkably talented band, Selway has also released solo work, with two great albums, Familial (2010) and Weatherhouse (2014). The melancholic Coming Up For Air is from the latter. The combination of gritty, haunting atmospherics with heavy reverb on Selway’s vocals evokes a feeling of total submersion underwater.

If you find Curio valuable, then feel free to share it with your network:

Curio is written by Oli Duchesne