⌾Curio #27 - Tenzing Norgay, the Mona Lisa & Yes

Beloved readers,

If the news cycle is filling you with angst, then I hope this newsletter acts as the mental equivalent of a brief escape to an Australian beach on a sparkling summer day.

Charles Meere - Australian Beach Pattern (1940)

I’m heading to Spain in a few days for a holiday and so won’t be sending out Curio for the next couple of weeks.

Stay safe,

- Oli

Tenzing Norgay and the Cost of Fame

“Wherever he is going, he is still en route. Everest, it seems, was just a way station.”

Tenzing Norgay reaching the top of the world. May 29, 1953

In 1954, a foreign correspondent for the New Yorker, Christopher Rand, wrote an extended profile of Tenzing Norgay, who, along with Edmund Hillary, became world-famous for summitting Mount Everest the year earlier. What I found interesting about the piece was how it details the personal difficulties faced by Tenzing after being propelled from humble obscurity to international stardom within such a short period of time. It seems to have put significant strain on Tenzing and his family and caused tension in his community as well as geopolitically. Rarely does a story provide such a stark lesson in the potential costs of fame.

Background and Upbringing

“Tenzing was born in a village called Thami, near Everest and at an altitude of fourteen thousand feet. His father owned yaks, and as a boy Tenzing herded them, often in pastures thousands of feet above Thami. He also went on caravan trips over the Nanpa La, a nineteen-thousand-foot pass near the western shoulder of Everest. From the start, he lived as close to Everest as a human being could.”

“When Tenzing was a boy, his heart was set on going to Darjeeling, but his father insisted that he stay home and herd yaks. He obeyed until he was nineteen, and then, in 1933, he and a few other young Sherpas fled to Darjeeling. For a couple of years, he made his way by renting out his pony and doing odd jobs, and in 1935 he was hired as a porter for a British Everest party. He went again in 1936 and again in 1938, learning the things that Sherpa guides must learn, including how to cook Western meals. His cooking is said to be good. The war suspended climbing for a decade, and it was not until 1952 that he tried Everest again, with the Swiss. He has tackled many other peaks as well. He has been through the mill. At times, one hears, he has been very down and very out, but long before his final success he was known as one of the most able Sherpa sirdars [group leaders] of this generation.”

Simpler times. Hillary and Norgay during their 1953 Everest expedition

After Everest

“[Climbing Everest] earned Tenzing a rest from his career as a climber, which had been arduous, and plunged him into a new career, involving contracts, publicity, and politics, which is a good deal more lucrative but which puts him under another kind of strain. Not only is he, like many famous men, unschooled in the ways of publicity but he deals haltingly with English, its lingua franca. Just keeping track of his own life, therefore, demands hard concentration. Tenzing complains that he has lost twenty-four pounds since climbing Everest, and he says—though he probably doesn’t mean it—that if he had foreseen the results, he would never have made the climb. His troubles are compounded by an element of jealousy in Darjeeling—he is to some extent a prophet without honor in his own country—and by a public disagreement, which he is well aware of, as to whether he is a great man or only an able servant. “I thought if I climbed Everest whole world very good,” he said recently. “I never thought like this.”

Tenzing is at everyone’s disposal. He has fixed up a small museum in his Darjeeling flat, exhibiting his gear, trophies, and photographs, and he stands duty there from ten in the morning to four-thirty in the afternoon. He is a handsome man, sunburned and well groomed, with white teeth and a friendly smile, and he usually wears Western clothes of the Alpine sort—perhaps a bright silk scarf, a gray sweater, knee-length breeches, wool stockings, and thick-soled oxfords. These suit him splendidly. Redolent with charm, Tenzing listens intently to questions put to him, in all the accents of English, by tourists who come to look over his display, and answers as best he can, often laughing in embarrassment. He charges no admission fee, but has a collection box for less fortunate Sherpa climbers, and he seems to look on the ordeal as a duty to the Sherpas and to India as a whole. The other day, I, who have been bothering him, too, remarked on the great number of people he receives. “If I don’t,” he answered, “they say I am too big.” And he scratched his head and laughed nervously.

Tenzing’s rise to fame caused some hard feelings between India and Nepal over the question of his nationality. On his trip to England with the Everest party, he took along passports of both countries, but now it is pretty well settled that he is Indian by choice and long residence, Nepalese by birth, and Sherpa—Tibetan, that is—by stock.”

Norgay and Hillary. Friends for life.

“After Tenzing climbed Everest, two purses were got up for him, each to buy him a house. One, a public subscription in Nepal, raised thirty thousand rupees (a rupee is worth twenty-one cents) on the supposition that the house would be in Nepal; when the Nepalese learned that he preferred to stay in Darjeeling, they sent him ten thousand anyway. Tenzing has no idea what they will do with the rest. The other purse was raised by the Statesman, a Calcutta paper, and Tenzing’s share was limited to twelve thousand rupees, anything over that being promised to the Himalayan Club for the use of other Darjeeling Sherpas. There have been further gifts to Tenzing, as well as fees of various sorts; Mitra [his personal assistant] says the grand total so far is something over sixty thousand rupees.

…

By Sherpa standards, [Tenzing has acquired] vast wealth. A porter gets three rupees a day, plus food, and a sirdar gets from five to ten rupees, plus food. Tenzing was paid eighteen hundred rupees, or a little less than four hundred dollars, for his two expeditions in 1952, and this must have been the Sherpa record for a year’s take. Now he makes many times that, and has thereby incurred an obligation to help other Sherpas. Most Sherpa climbers past their prime have a hard lot, for few of them save any money. The most famous Sherpa mountaineer of the twenties and early thirties, Lhakpa Chedi, who was taken to England and France and fêted, and whose name, a British climber once said, should be written in letters of gold alongside Mallory’s, is now a doorman for a Calcutta store, erect but dim-looking. And he has fared better than most elderly Sherpas, many of whom are derelicts. Tenzing himself, now in his forties, is near the age when Sherpa climbers must slacken off, and that he can do so in such unprecedented circumstances is inevitably resented. The horse I saw him riding had cost eight hundred rupees, more than most Sherpas have ever had at one time. Some of Tenzing’s neighbors think he has gone high-hat, and do not hesitate to say so. The other evening, as I was walking past his place, a couple came walking toward me. Two dogs rushed out, barking.

“Tenzing’s dogs,” the lady said.

“Has he got dogs now?” asked the man, as if discovering the limits of vanity."

You can read the full profile of Tenzing Norgay here.

When the Mona Lisa was Stolen

On August 21, 1911, a worker at the Louvre called Vincenzo Peruggia hid in a cupboard overnight and took the Mona Lisa off the wall, removed it from the frame, rolled it up and escaped with it hidden under his overalls.

The next morning, a young artist came to the museum to sketch the Da Vinci portrait but instead found four bare hooks on the wall.

Where the Mona Lisa should have been

When the news broke, it shocked the world. France sealed its borders and sent photos of the painting to newspapers around the globe. A number of artists in Paris were arrested on suspicion of being involved, including Pablo Picasso, but the authorities kept hitting dead ends.

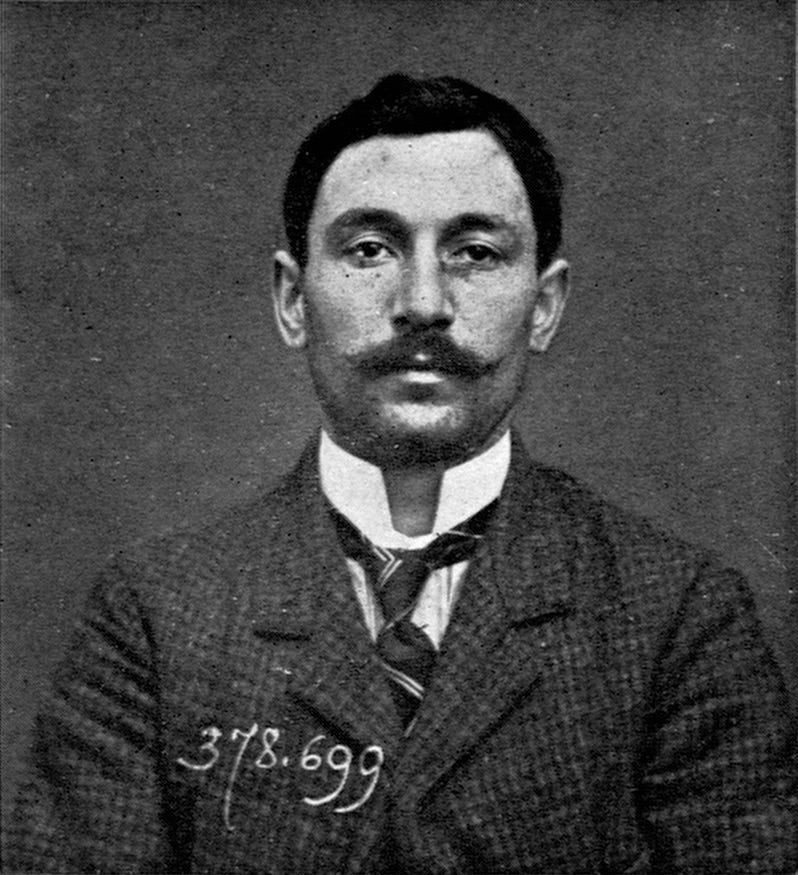

Vincenzo Peruggia had the Mona Lisa on his kitchen table for two years

Peruggia had the artwork on his kitchen table for two years. As an Italian nationalist trying to right a perceived artistic injustice, he falsely believed that the Mona Lisa was looted from Italy by Napoleon in the early nineteenth century. Peruggia was only caught when he tried to sell it to a museum in Florence.

The recovery of the Mona Lisa. The world breathed a sigh of relief.

In the two years that the painting had been missing, the Mona Lisa had become the most recognizable piece of art in the world.

Lee Cheshire, author of Key Moments in Art, states:

“The Mona Lisa was already much loved, but the publicity around the theft made it truly iconic as its image was reprinted millions of times in newspapers, which had recently started to regularly print photographs. It was perhaps the first artwork to pass into popular culture and the start of the era of mass reproductions of paintings.”

Noah Charney, professor of art history and author of The Thefts of the Mona Lisa, argues:

"If a different one of Leonardo's works had been stolen, then that would have been the most famous work in the world -- not the Mona Lisa. There was nothing that really distinguished it per se, other than it was a very good work by a very famous artist -- that's until it was stolen. The theft is what really skyrocketed its appeal and made it a household name."

Yes

Progressive rock band, Yes, released the song Roundabout on their 1971 album, Fragile. It was the group’s first mainstream hit and is a showcase of their extraordinary musicianship, particularly the virtuosic keyboard work of Rick Wakeman. The memorable opening to the track was produced by Wakeman playing a note on the piano that was recorded and played backwards, creating the feeling that the song is rushing towards you. The lyrics describe a psychedelic car journey and were inspired by the band driving through the Scottish countryside while on tour. I was introduced to Yes as a young boy by my Dad, as they are one of his favorite bands. What I love about them is their spirit of experimentation and willingness to push musical boundaries.

Fragile features the cover art of Roger Dean, famous for his exotic fantasy landscapes

“Incuriosity is the oddest and most foolish failing there is”

- Stephen Fry

Curio is an email newsletter for curious minds seeking an escape from the noise of the news cycle. It is put together by Oli Duchesne