⌾Curio #36 - Hanya Yanagihara, Victorian Beards & The Cinematic Orchestra

Last Friday I witnessed my first shooting. I was working at my desk in my bedroom overlooking Maujer St in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The sun was streaming through the window and a comfortable breeze drifted in. It was the first warm day of the year and there was a buzz of activity outside.

It was just after lunchtime and I was tapping away at work emails when I heard two explosive bangs. I turned and saw a group of about ten men across the other side of the road. They were all frozen except for one young guy with a black bandana as a COVID mask and a pistol in his right hand. He turned and strutted away as if it were nothing. The rest of the group stood in shock and then scampered, leaving the victim sitting slouched on the cement. He was alive but wounded in the stomach, his white t-shirt splotched with red marks.

Within what seemed only a minute, the street was swarming with NYPD officers and detectives. They cordoned off the area with police tape and created a crime scene. They spoke on walky-talkies, scribbled in note pads and questioned witnesses. A couple of the officers helped the slouched victim by keeping pressure on his stomach until the ambulance arrived.

Over the next few hours nothing much happened, just a lot of standing around. Then at about five-thirty the officers abruptly started packing everything up and taking down the police tape. Within a few minutes the area was clear and back to the way it was, with nothing to suggest someone had been shot in the stomach a few hours earlier.

Curious to know what had happened, I hurried downstairs to ask before the remaining NYPD cars left. I sidled up to an officer rolling up the tape and asked in my most earnest voice, “Did you get him?”

“Excuse me, sir?” he said, baffled by my strange accent.

“Did you catch the guy?”

“That’s not something we can disclose. Please keep walking, sir,” he said, unimpressed.

I kept walking.

—

Asher Brown Durand - Summer Afternoon (1865)

—

I’m Oli Duchesne and you’re reading Curio, the newsletter for curious minds seeking a brief escape from the noise of the news cycle.

Enjoy your weekend and stay safe,

Oli

Hanya Yanagihara on Friendship

“Friendship is one of our most treasured relationships, but it isn’t codified and celebrated”

Perhaps the hardest part of this lockdown for me has been the forced separation from friends. Phone calls and glitchy Zoom chats haven’t quite cut it.

A writer who spends a lot of energy focusing on the underrated and underappreciated power of friendship is Hanya Yanagihara, the author of A Little Life (2015). Yanagihara’s novel is a heartwrenching story of four men over a period of decades, starting just after college and continuing into their middle age. The book is a meditation on how close friendship — with its selflessly pure commitment to each other’s well being — can provide irreplaceable solace during life’s ups and downs.

Yanagihara was born in LA and grew up in Hawaii. She is the editor-in-chief of T: The New York Times Style Magazine. Wrote the A Little Life at night while she worked full time

—

In an interview with Foyles after the book’s release, Yanagihara said:

“I think friendship has always been essential to who we are as humans — it's just that it's a relationship that's never been considered as important as it is. For centuries (and, to a lesser extent, today), friendship was the only relationship that existed outside society's demands; it was the only relationship you chose, rather than had bestowed upon you. When you are a spouse, a parent, an employee, a citizen, you live by certain rules, some of them dictated by law, others by social expectations. But friendship is the one relationship available to us in which the laws and limits are defined only by the participants. It can't be codified, which means it's ever shifting, ever vulnerable, ever electric, and ever demanding. When we choose a friend, and choose the terms of that friendship, we are exercising our rights of freedom and our rights as a human. One of the things two of the characters in this book learn is that their version of what friendship is needn't be anyone else's, and that every friendship is unique in its shape and form, and that how we express friendship is often an expression of what we need most from another person, and are forever searching for, even if we don't know it.”

In another interview with Bookanista, she said:

“The very word friend is so unsatisfying in many ways, because it means everything and nothing. How do you distinguish between someone who means the world to you, and someone you’re only friends with on Facebook? It’s tough. How do you announce to society the profundity of what you and that person share except by saying, ‘They’re my boyfriend, or my girlfriend.’ I’m wondering how many of these relationships change due to the tyranny of language, the paucity of terms we have to define them.”

Friendship in A Little Life

The following passages are some of the best bits on friendship found in the novel:

“Why wasn’t friendship as good as a relationship? Why wasn’t it even better? It was two people who remained together, day after day, bound not by sex or physical attraction or money or children or property, but only by the shared agreement to keep going, the mutual dedication to a union that could never be codified. Friendship was witnessing another’s slow drip of miseries, and long bouts of boredom, and occasional triumphs. It was feeling honored by the privilege of getting to be present for another person’s most dismal moments, and knowing that you could be dismal around him in return.”

—

“The only trick of friendship, I think, is to find people who are better than you are—not smarter, not cooler, but kinder, and more generous, and more forgiving—and then to appreciate them for what they can teach you, and to try to listen to them when they tell you something about yourself, no matter how bad—or good—it might be, and to trust them, which is the hardest thing of all. But the best, as well.”

—

“Wasn’t friendship its own miracle, the finding of another person who made the entire lonely world seem somehow less lonely?”

Victorian Beards

From the mid-seventeenth century for almost two hundred years, facial hair was barely seen on men’s faces across Europe. The male aristocratic aesthetic involved wigs and makeup. Beards became associated with the unrefined and uneducated, whereas learned and polite gentlemen were always clean-shaven.

Aristocratic gentlemen in the 17th century, from Nicolas de Largillière’s “St. Genevieve asks for rain for the Abbey Sainte-Geneviève" (1696)

—

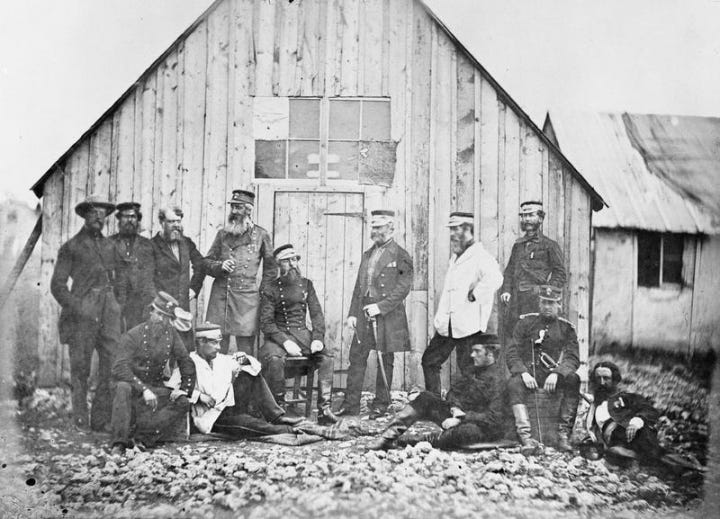

Crimean War (1853 - 1856)

In an interesting historical twist, the Crimean War was what brought the beard back into mainstream acceptability. Beards had been banned in the British army until this time, but the combination of the freezing Eastern European winters and the lack of shaving soap led the British army to relax its rules. When the British soldiers returned home victorious most of them were sporting glorious facial hair.

British soldiers in the Crimean War (1853-56). The British army relaxed its rules on facial hair and the men took full advantage

—

Beards had become a symbol of heroism and men who had never seen military action starting growing them. Within a few years, it was rare to see a beard-free male face in Victorian Britain.

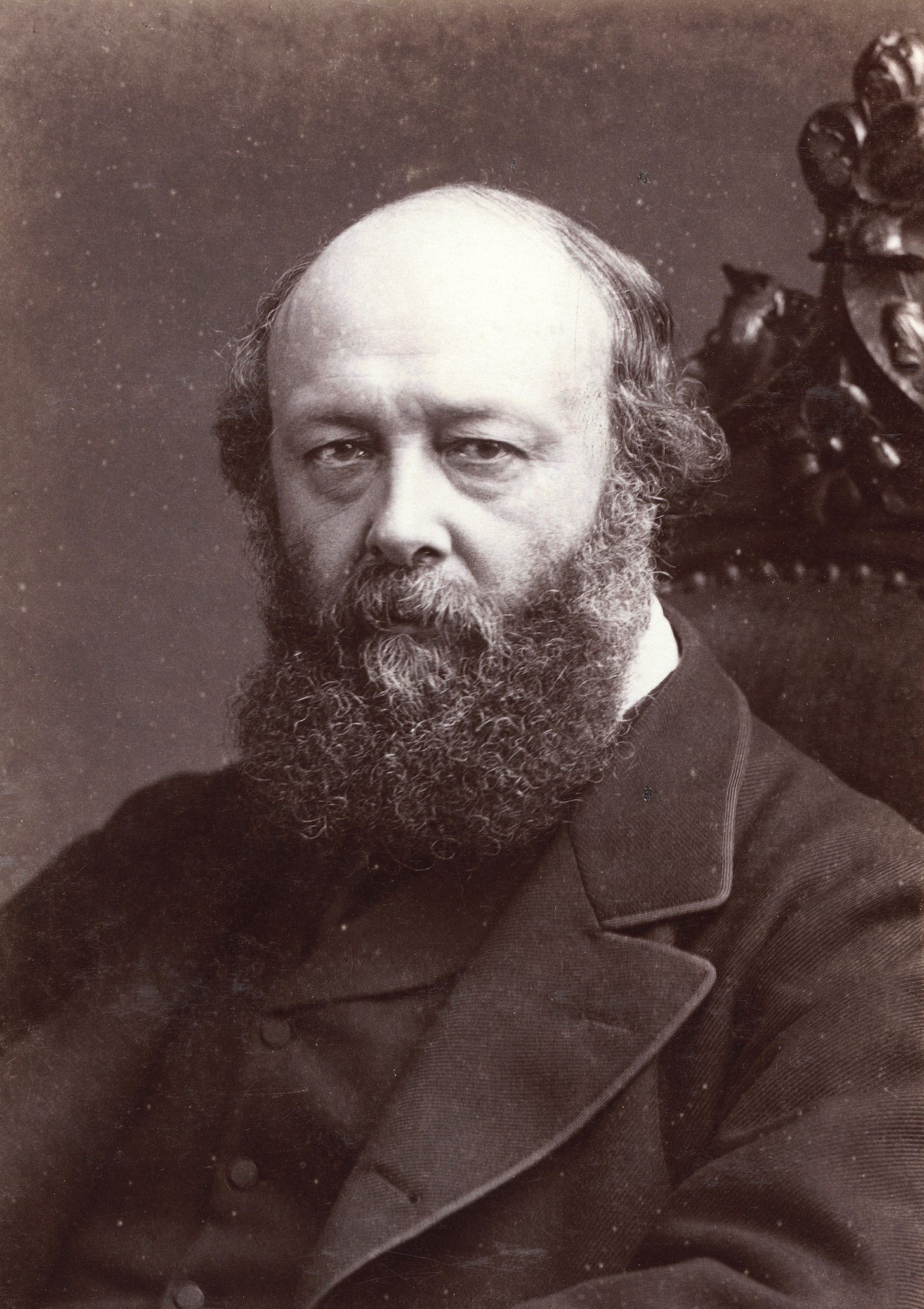

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury. Prime Minister of the UK three times during the 1880s and 1890s

—

Facial hair became a marker of elegance and distinction: the more preposterous, the better.

Charles Dickens (1812 - 1870)

—

In the United States, thick facial hair returned during this time too, partly due to the influence of British magazines.

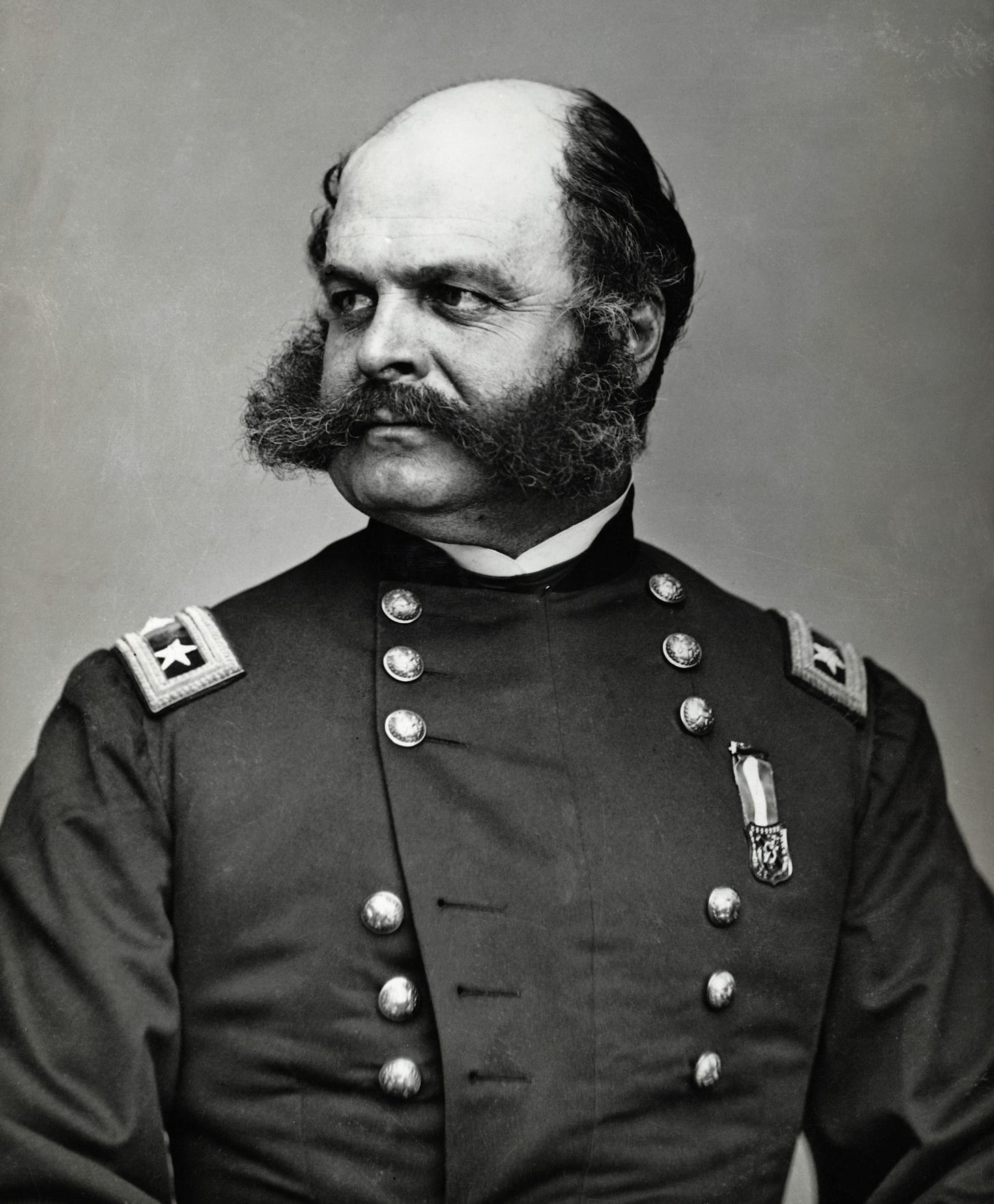

During the American Civil War of 1861-5, the word "sideburns" was invented, as a tribute to Maj Gen Ambrose Burnside (1824 - 1881), a man with luscious whiskers

—

For many American men, it was also a practical decision to stop shaving. Although the “safety razor” had been around since the eighteenth century, they were difficult and time-consuming to use (usually requiring a trip to the barber) and often resulted in cuts and infection.

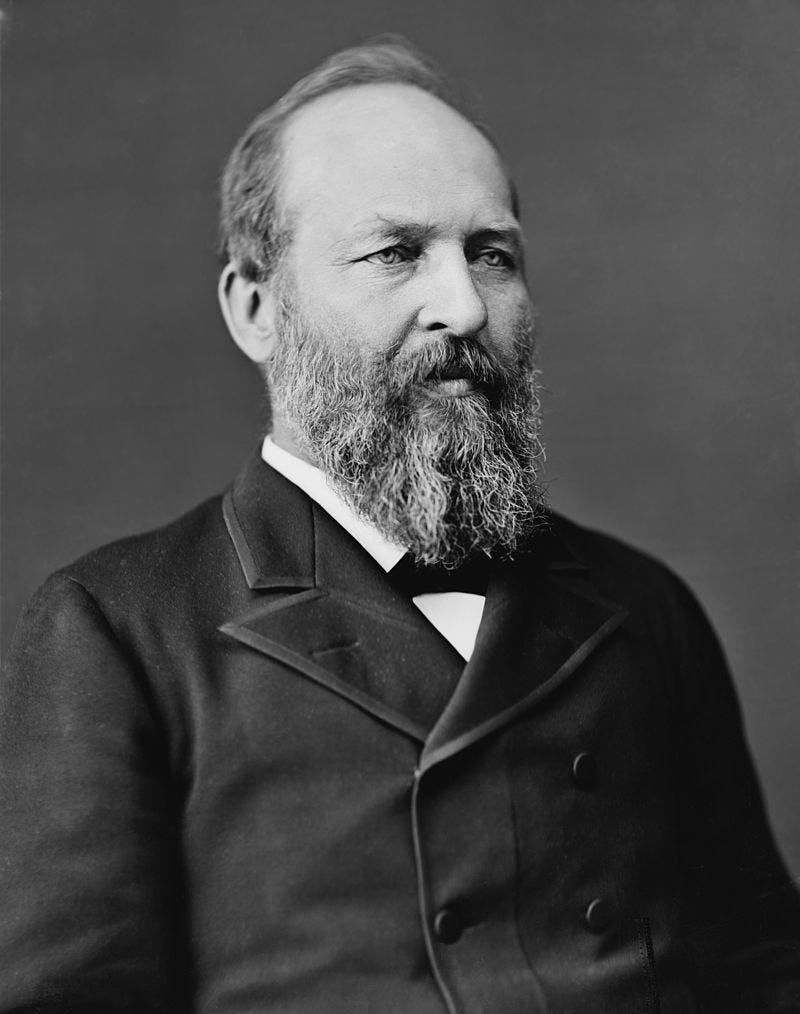

James Garfield. 20th President of the United States

—

This trend of bushy beards and unruly sideburns started to change in the late nineteenth century when fashionable young men in London were returning to their barbers for a daily shave. As a result, facial hair came to be associated with the conservative, older generation.

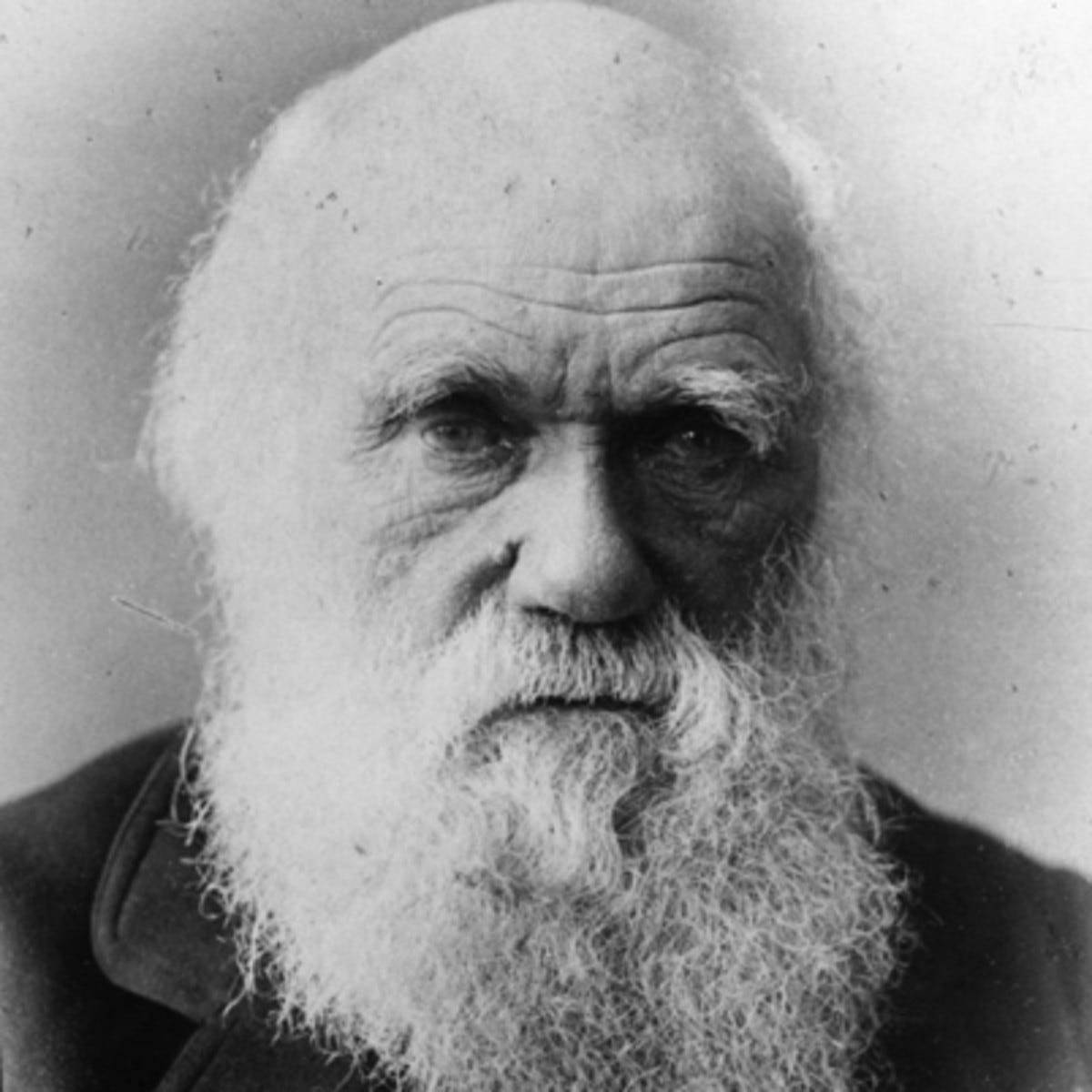

Charles Darwin (1809 - 1882)

—

Gillette’s Razor

In 1895, the American inventor, King Camp Gillette, created the first disposable razor blade. A patent was granted in 1904 and it quickly became a sensation. Men didn’t need to go to the barber anymore and were able to safely shave at home.

Hairy faces started to disappear during the early twentieth century. The era of exuberant beards, ludicrous whiskers and bristling moustaches was largely over.

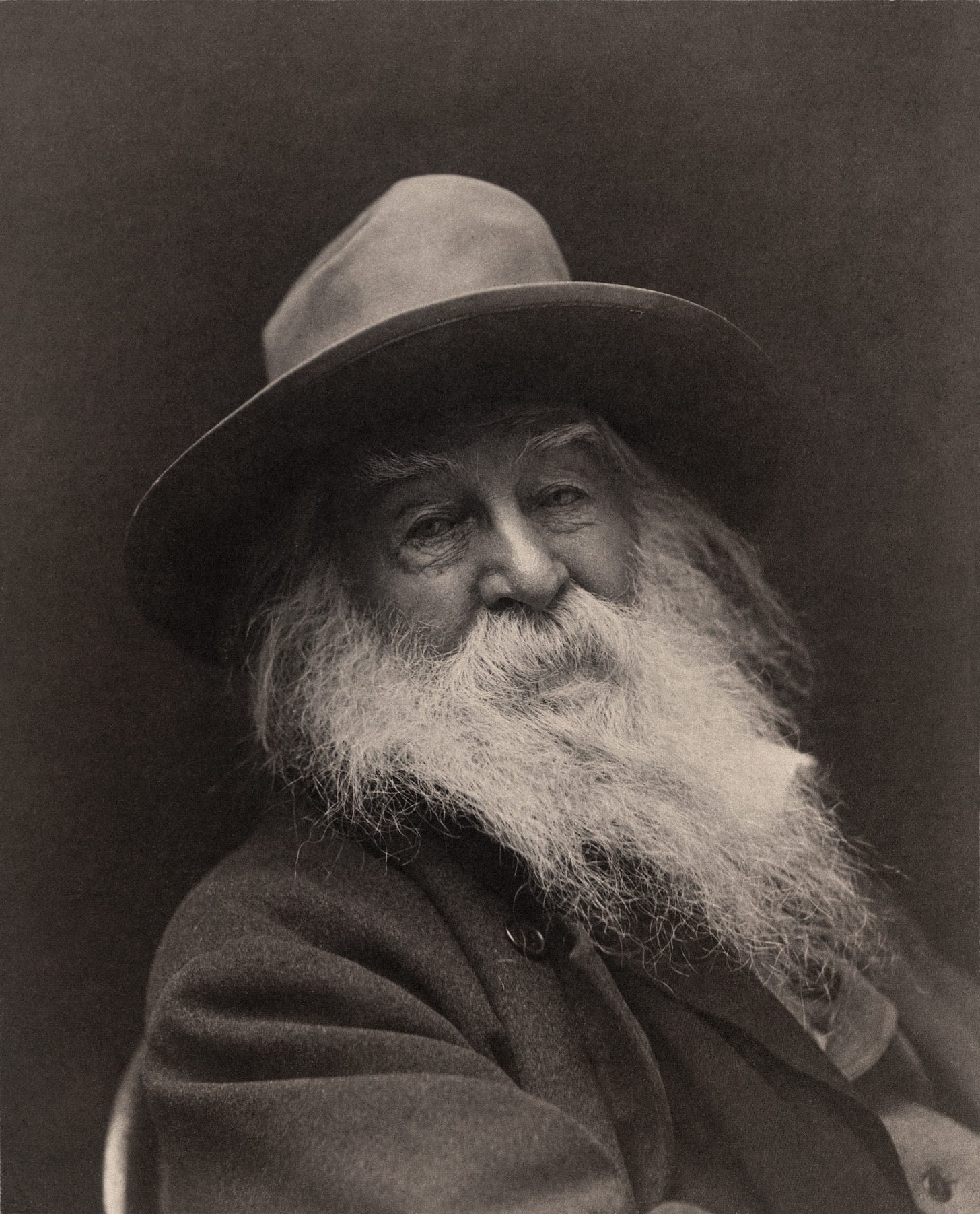

Walt Whitman (1819 – 1892)

—

The Cinematic Orchestra

To Build A Home by The Cinematic Orchestra is a song you’ve probably heard before. It’s been used in countless TV shows, movies, and advertisements. I remember first hearing it in a Schweppes ad in 2008. The track was released in the group’s third studio album, Ma Fleur (2007) and features the gracefully haunting vocals of Canadian singer-songwriter Patrick Watson. To Build A Home is an epic, soul-stirring piano ballad that climaxes around Watson’s sublime falsetto.

“Remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet. Try to make sense of what you see and wonder about what makes the universe exist. Be curious.”

- Steven Hawking

Curio is a newsletter for curious minds seeking an escape from the noise of the news cycle. It is put together by Oli Duchesne