⌾Curio #40 - Maya Angelou, Pre-Industrial Sleeping Habits, St Germain

Welcome back dear readers to another edition of Curio. If the news cycle is getting you all worked up, then I hope this newsletter acts as the mental equivalent of sitting by a tranquil river on a Saturday afternoon with the sun on your back and your feet dangling in the water.

Georges Seurat - Bathers at Asnières (1884)

—

I’ll be away next week and the following week is the 4th of July long weekend, so Curio will be back the Friday after that. I hope you’re staying safe and healthy.

See you in a few weeks,

Oli

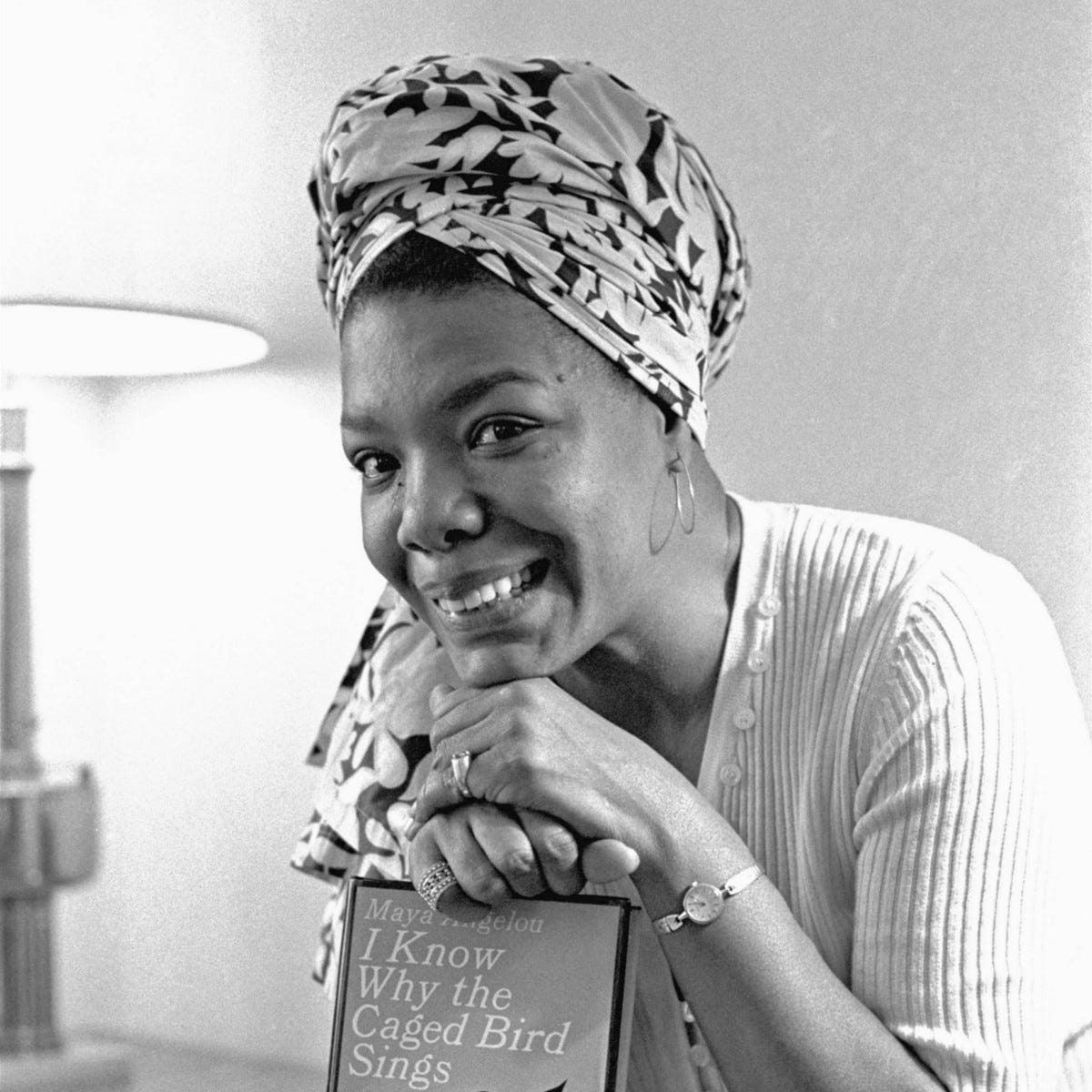

Maya Angelou and the Caged Bird

One of the most powerful poems ever written exploring the jagged contrast between freedom and oppression is “Caged Bird” by Maya Angelou (1928 – 2014), the famous poet, memoirist and civil rights activist. The name of the poem echoes the title of her 1969 autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, about her childhood growing up in the South during segregation. Using an evocative metaphor of two birds, one free and the other stuck in a cage with its wings clipped, Angelou highlights the humiliating spiritual suffocation that comes from being denied freedom.

James Baldwin describes Angelou as approaching her life with “luminous dignity”

—

One reason I find the poem so potent is that it shows how hard it can be to break the shackles of oppression. For instance, a bird with clipped wings can not possibly survive outside a cage, so whoever put it there can justify keeping it in the cage to keep it safe. In other words, the bird’s imprisonment becomes self-perpetuating.

Another striking element of the poem occurs in the second stanza (“can seldom see through his bars of rage”), which shows how the cage doesn’t just keep the bird trapped, it also changes the bird too. Captivity robs the bird of its very self.

I hope you find Angelou’s piece as compelling as I do.

—

Caged Bird

A free bird leaps

on the back of the wind

and floats downstream

till the current ends

and dips his wing

in the orange sun rays

and dares to claim the sky.

But a bird that stalks

down his narrow cage

can seldom see through

his bars of rage

his wings are clipped and

his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

The free bird thinks of another breeze

and the trade winds soft through the sighing trees

and the fat worms waiting on a dawn bright lawn

and he names the sky his own

But a caged bird stands on the grave of dreams

his shadow shouts on a nightmare scream

his wings are clipped and his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

—

Carel Fabritius - The Goldfinch (1654)

—

Pre-Industrial Sleeping Habits

In the twenty-first century, most of us aim to have seven to eight hours of uninterrupted sleep per night. However, it turns out that historically, this is a relatively recent phenomenon.

Henry Fuseli - The Nightmare (1781)

—

In 2005, historian Roger Ekirch published At Day's Close: Night in Times Past, which was the culmination of over twenty years of research into the history of sleep. Drawing on more than five hundred sources, from Homer's Odyssey to court documents from medieval Britain and anthropological accounts of tribes in Nigeria, Ekirch outlines how for most of history people slept in two distinct installments: "first sleep" and "second sleep".

Henri Matisse - Portrait of a Sleeping Marguerite (1920). One of the earliest references to the practice of sleep being split into two periods can be found in The Odyssey, in which Homer refers to the “first sleep”

—

Before the rise of electricity, most people would go to bed when it got dark, sleep for around four or five hours and then wake up in the middle of the night. The next hour or two would be dedicated to activities such as reading, relaxing, sex, chores around the house and even visiting neighbors. Following this, people would settle down for a second period of slumber until dawn.

Rembrandt - Old Man Sleeping (1629). A doctor's manual from sixteenth-century France advised couples that the best time to conceive was "after the first sleep."

—

Ekirch argues this practice of bi-modal sleep started to change in the industrial revolution, with its improvements to street and household lighting. This led to people staying up much later and sleeping in one long stretch until morning.

Picasso - Head of a Sleeping Woman (1907). In the early 1990s, psychiatrist Thomas Wehr conducted an experiment where he exposed a group of people to darkness for fourteen hours every night for a month. By the fourth week, most of the participants were sleeping in two phases: sleeping for about four hours, then waking for one to three hours before falling into a second four hour sleep. His study suggests two-phase sleep has some basis in biology

—

By the early twentieth century, the idea of two periods of sleep had disappeared.

St Germain

Ludovic Navarre (St Germain) is a French acid jazz musician who helped pioneer the fusion of house and jazz music. This track, Rose Rouge, from the fantastic album Tourist (2000), samples the sultry voice of Marlena Shaw (“I want you to get together/put your hands together one time”) and features a beguiling and relentless drum, bass and piano loop. Paired with old footage of New York in the below video clip, it’s a real treat. If you like this, then check out this great house remix by Joris Voorn.

“Anyone who stops learning is old, whether at twenty or eighty. Anyone who keeps learning stays young.”

- Henry Ford

Curio is a newsletter for curious minds seeking an escape from the noise of the news cycle. It is put together by Oli Duchesne