⌾Curio #42 - Bertrand Russell, The Conformist & George Gershwin

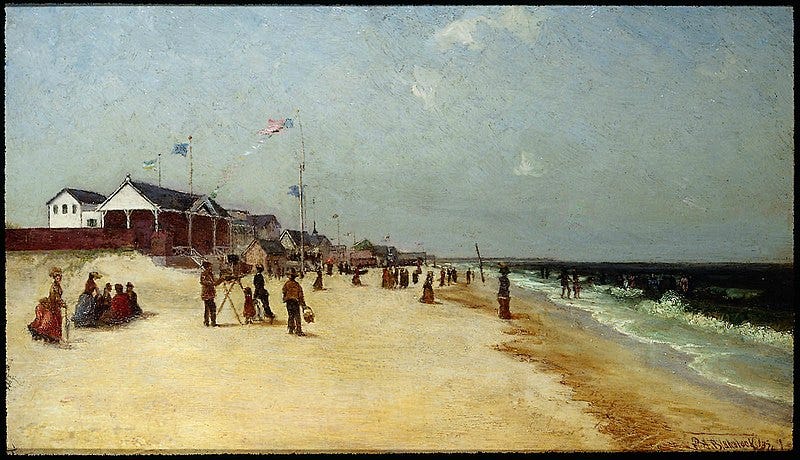

Before I moved to New York I didn’t know it had beaches. Sure, I’d heard of the Hamptons, but I never knew there were beaches within the city of New York itself. The two most popular options in summer to escape the muggy heat are Coney Island Beach near the famous and faded amusement park in the southern part of Brooklyn, and Rockaway Beach in deep Queens, a few stops on the subway past JFK airport. Rockaway is where I like to go. It’s a seemingly never-ending stretch of sand broken up every one hundred meters or so by a rock wall, which separates the beach into sections. Parallel to the sand is a wooden boardwalk with a parade of people running, cycling and rollerblading. Spaced out along the boardwalk are a number of bars, which in pre-plague days would be overflowing with sandy and sunburnt patrons cheerily gulping down beers and cocktails.

Ralph Albert Blakelock - Rockaway Beach (1870)

—

Admittedly, Rockaway isn’t the most picturesque of places — it’s a bit shabby around the edges, the water can be murky and the proximity to the airport means a consistent flow of low-flying planes. But it does have a certain, unpretentious charm and on warm Saturdays during the summer months can have a genuinely festive atmosphere. I’m also yet to find a better cure for a paint-stripping hangover than submerging myself in its refreshing slate blue water. Most importantly, however, Rockaway is completely removed from the chaos of the city. Spending the day there feels like taking a mini-vacation. I’m so glad it exists.

Have a wonderful weekend!

- Oli

There was an unfortunate issue last week with the tech platform responsible for distributing my newsletter. It meant about forty subscribers didn’t receive Curio #41 on Eric Pickersgill, Nicaraguan Sign Language and Philip Glass. If you didn’t receive last week’s edition, you can read it here.

Bertrand Russell’s Changing Beliefs and Unchanging Hopes

The below interview from 1952 with Bertrand Russell is a treat. It was filmed just before his eightieth birthday and offers a fascinating glimpse into the man and his extraordinary life. Russell was one of the intellectual behemoths of the twentieth century: a philosopher, mathematician, historian, and author of more than sixty books. In 1950, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought."

Highlights of the video include:

Russell, born in 1872, discussing how much the world has changed in his lifetime: “It’s very difficult for anybody born since 1914 to realize how profoundly different the world is now to what it was when I was a child. The change has been almost unbelievable”

He explains how his parents died when he was an infant so he was raised by his grandparents. His grandfather was born during the early years of the French Revolution and was a member of British parliament when Napoleon was on the throne. He visited Napoleon in Elba in 1814. I was blown away by the humbling sense of time and perspective I felt watching this clip: here we are in 2020 watching a 1952 interview with a polymath born in 1872, who talks about how his grandfather visited Napoleon on Elba in 1814. When speaking about his grandfather (who was Prime Minister twice in the mid-nineteenth century), Russell says: “I remember him quite well. But, as you can see, he belonged to an age that now seems rather remote.”

In 1920, Russell traveled to Soviet Russia as part of an official delegation sent by the British government to investigate the effects of the Russian Revolution. While in Moscow he met Vladimir Lenin and had an hour-long conversation with him

In 1921, he taught philosophy for a year in Peking (Beijing) and thoroughly enjoyed it

Russell, who came from an aristocratic background, mentions how when he was growing up, there was an austere approach to living by people of even great wealth that had since disappeared: “my grandmother, until she was over seventy, would never sit in an armchair until after dinner. Ever.”

He describes his life to that point as “eighty years of changing beliefs and unchanging hopes”

The Cinematography of The Conformist

A few weeks ago I watched Bernardo Bertolucci’s visual masterpiece, The Conformist. Set in Mussolini’s Italy during the 1930s, the plot centers on a man, Marcello, who wants, above all, to live a “normal” life.

In order to fit in and conform with society’s expectations, he marries a woman he despises, pretends to be a believing Catholic and joins the dominant National Fascist Party. He gets a job with the secret police, which seeks to crush opposition to fascism and eliminate dissidents.

His first assignment is the assassination of a vocal opponent of the regime living in Paris, who happens to be Marcello’s former university professor. Using his honeymoon as a cover, the newlyweds arrive in Paris where Marcello makes contact with his old professor. To complicate matters, Marcello falls in love with the professor’s wife and they have an affair. Throughout the film, Marcello wrestles over whether he will go through with the murder.

While the story and acting are certainly compelling, the film is famous for the groundbreaking cinematography of Vittorio Storaro. His use of space, angles, architecture and light was revolutionary and is still studied today.

Storaro was intrigued by the psychological impact of different colors on our emotions and perceptions: he used a bright palette of golds and blues to evoke Paris, contrasting it with the shadowy greys of fascist Rome.

Francis Ford Coppola was so impressed with what he saw in The Conformist that he recruited Storaro to help with “The Godfather Part II” and “Apocalypse Now”, for which he received the first of three Academy Awards for Best Cinematography.

An episode of The Sopranos, called “Pine Barrens”, is an extended homage to The Conformist.

—

The following video is a short tribute to the gorgeous cinematography of the movie.

George Gershwin

The below is a marvelous visual representation of the playful song Liza by American composer, George Gershwin (1898 – 1937). It was created by French visual artist Bastien Dupriez who creatively uses colors and shapes to interpret the sounds of the music. On how he got the synchronization so perfect, Dupriez responded, “I listen to the music very very slowly, like frame by frame.”

“The more I read, the more I acquire, the more certain I am that I know nothing.”

- Voltaire

Enjoying Curio? If so, the good news is there are two main ways you can support it each week:

‘Like’ it by clicking the love heart underneath the title. The more ‘likes’ Curio receives, the more public exposure it gets on various online lists and forums

Forward it to friends or colleagues you think may also enjoy it. They can sign up below:

Curio is a newsletter for curious minds seeking an escape from the noise of the news cycle. It is put together by Oli Duchesne