Curio #7 - Frederick Olmsted, Marchetti's Constant & Chesus

Welcome back to another edition of Curio, a newsletter for curious minds who crave a brief break from the exhausting news cycle.

Love Curio? Then forward it to three friends.

Hate Curio? Then forward to three mortal enemies.

Either way, they can sign up here:

Until next week!

Oli

Frederick Olmsted’s Philosophy of Parks

What do Central Park, Prospect Park, Stanford University, the University of Chicago, the gardens of the Biltmore Estate (the largest house in America), the space around the United States Capitol, as well preservation plans for Niagara Falls and Yosemite National Park all have in common? They represent just a fraction of the public parks, private gardens, university campuses and public spaces designed by the father of landscape architecture, the prolific Frederick Olmsted.

Early Life & Inspiration

Frederick Olmsted was born in 1822 to a wealthy family in Connecticut and after finishing school he traveled the world as a merchant seaman before settling down to work as a gentleman farmer in Staten Island. At twenty eight, he went to England and became fascinated with their public gardens and parks, the likes of which did not exist in America. In particular, Liverpool’s Birkenhead Park, which had just opened and was the first publicly funded park in England, transformed Olmsted’s idea of shared space.

Birkenhead Park, Liverpool

In his subsequent book, Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England, he wrote:

“Five minutes of admiration, and a few more spent studying the manner in which art had been employed to obtain from nature so much beauty, and I was ready to admit that in democratic America, there was nothing to be thought of as comparable with this People’s Garden.”

Olmsted was amazed by the fact that Birkenhead Park seemed to be enjoyed “about equally by all classes”. In the US at the time, most parks were either on private estates or behind locked gates and reserved for the wealthy.

The gates of New York’s Gramercy Park

The book was well received and when he arrived back in America in 1852 he was offered a job as a journalist for the New York Times. Olmsted then spent the next five years on an extensive research journey through the American South, documenting the economic and social conditions of the slave states.

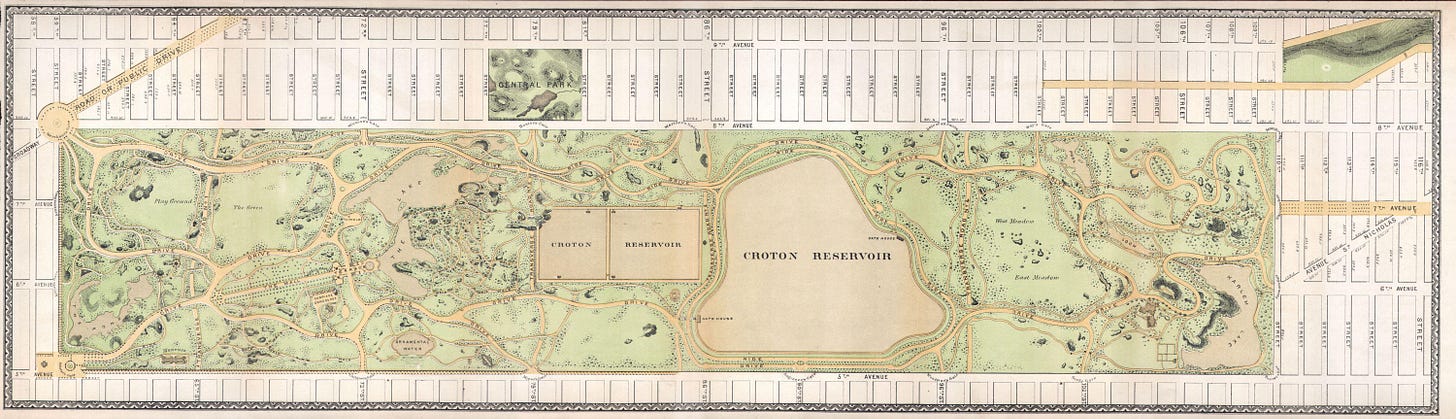

However, his passion for public parks remained and in 1858, Olmsted partnered with Calvert Vaux, a trained architect, and together they entered a competition to design Central Park. They won the prize with the below plan:

Olmsted and Vaux’s submission

Olmsted’s Radical Philosophy

Olmsted’s believed, controversially at the time, that a public park should be:

Democratic

An egalitarian space where all social classes intermingle

A playground, not ceremonial

It ought to be enjoyed

An escape from the city

Journalist Adam Gopnick writes that Olmsted wanted the “deliberate absence of orientation, of clear planning, of a familiar, reassuring lucidity.”

It’s easy to get lost in Central Park and that’s the point

Faithful to the character of the natural terrain

Beauty does not come from planting exotic flowers and trees, but rather from the general effect created by the space

Complementary the city to which it belongs

Since New York was cramped, crowded and meticulously gridded, he thought Central Park should be purposely disordered, haphazard and with wide open spaces

A unified work of landscape art

Gopnick: “The Park as Olmsted and Vaux imagined it was an almost entirely fantastic place, a kind of Ruskinian Disneyland. They decided to build, on approximately seven hundred and seventy acres of smelly swamp and rocky outcroppings and weedy trees, an orchestrated fantasy of nature — meadows and rock bluffs, ponds and wooded hillsides…”

Gopnick describes the impact of Olmsted’s philosophy:

“Central Park is without a central place. It has many centers, and was meant to: the Sheep Meadow, the Mall, the Reservoir — all provide an experience of the center without actually being one. This aspect of the Park troubled people. Some of the wealthy New Yorkers who were involved in the project hated it; the slack structure drove them crazy. In the years from 1858 to 1861, as the Park was being built, most of Olmsted’s energy was spent resisting the steady, sometimes overwhelming pressure to make the Park look like a park: to give it shape, a layout, a fixed form.”

“August Belmont, one of the richest and most powerful men in New York, seconded a plan, created by another rich man, Robert Dillon, to have a grand “Cathedral avenue,” a single central allée of trees, run, Versailles style, from end to end of the Park. Olmsted’s objection was not merely that such an allée would break the illusion of a forest in the middle of the city but that it would give a false, forced, European-style unity to what was meant to be a non-centered, American design.”

Central Park today

Marchetti’s Constant

In 1994, Italian physicist, Cesare Marchetti, published a paper titled Anthropological Invariants in Travel Behaviour. In it, he described an idea that has since become known as Marchetti’s Constant: that people have always been willing to commute from their home to work for about 30 minutes each way.

The exact figure varies from city to city and from person to person, but Marchetti found that from ancient Greece until today, the average commute time has stayed relatively similar, despite radical technological improvements in transport and the size of cities increasing.

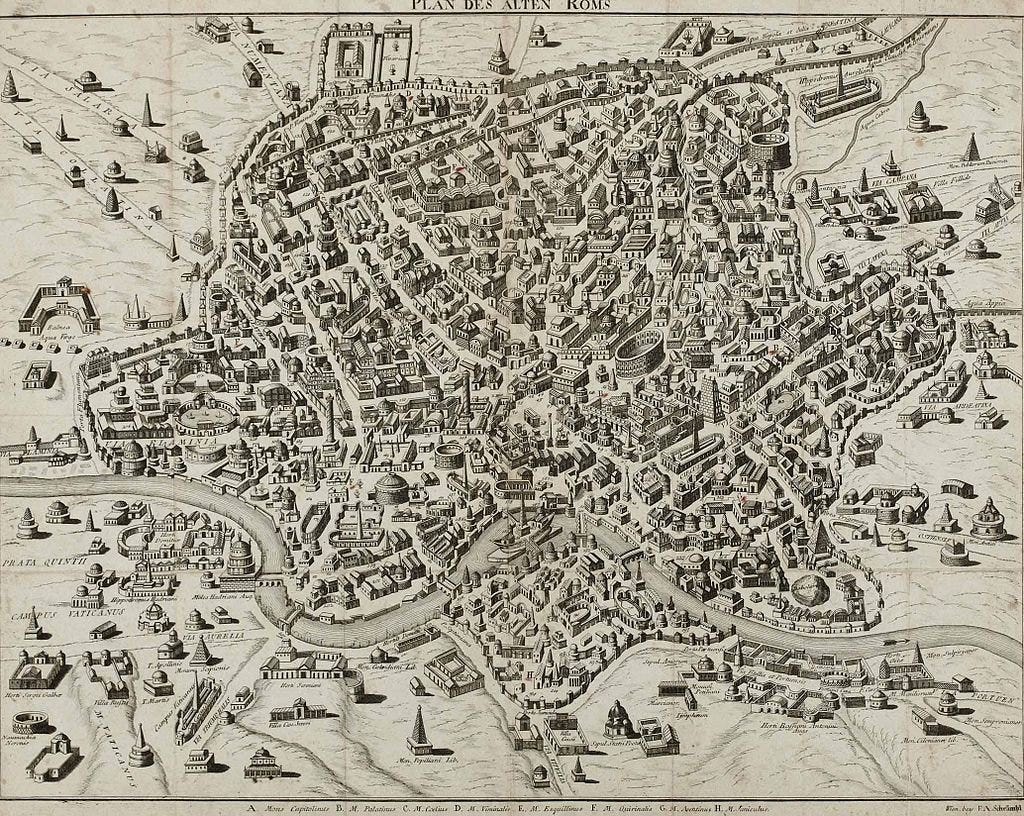

Ancient Rome was about five kms across, or the maximum distance most people can travel in an hour on foot. To walk from the edge to the middle would take about 30 minutes

The industrial revolution was the first time that commuting to work was no longer limited to walking or horsepower. As a result, London in the 19th century expanded in size as wealthy people were able to live on the fringes of the city and take a steam train into work. Compare that to the size of ancient Rome and 14th century Paris, where people were confined to walking.

However, steam trains were relatively expensive and it wasn’t until the invention of trams (known as streetcars in North America) and modern bicycles in the late 19th century that the middle classes had a cost-effective way of living in suburban areas and getting to work in about 30 minutes.

The car then changed everything again and the size of cities exploded by the mid 20th century.

Marchetti’s Constant means:

That it’s the speed of transport more than anything else that influences the physical structure of cities

Despite radical technological improvements, the length of your daily commute is probably similar to someone from ancient Rome.

Chesus

Chesus, who now releases under his name, Earl Jeffers, is a producer based in Cardiff. He makes the type of upbeat, funky and disco-laced house music that is impossible not to love on the dance floor. Special was released in 2013 and samples the 1976 soul banger Darlin' Darlin' Baby by The O'Jays.

Thanks for reading! Have a great weekend :)